Your Girlfriend, the Algorithm: What Parasocial Fans Got Wrong About Ari Kytsya

What the Girthmasterr drama reveals about commodified intimacy and the illusion of access.

People are mad that their favorite sex worker is, it turns out, not the smooth-talking seductress they imagined her to be; but, in fact, kind of an awkward person.

Ari Kytsya’s latest OF video is going viral. Not because it was particularly good, but rather, because it was unexpectedly lackluster. Her newest film, which was teased and promoted on TikTok for weeks prior, features her and fellow influencer Girthmasterr, going at (what looks like) twenty minutes of clumsy, amateur sex, filmed on a wobbly iPhone camera at 0.5 lens.1

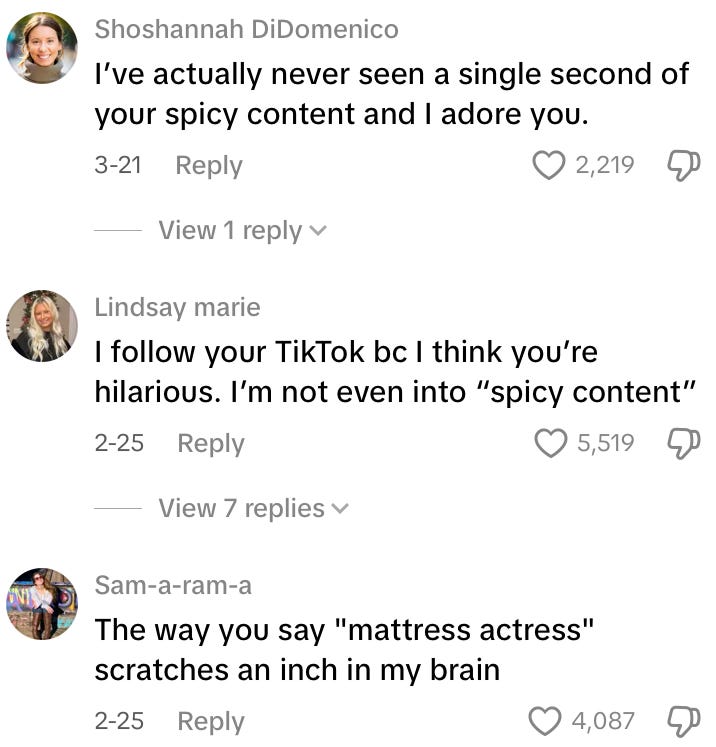

Since then, fans have been flooding her comments with accusations of “bad acting,” “seeming nervous,” and “ripping them off.” In short, for not living up to the hype.

Setting aside my own judgments of the film, I have to ask: what is it, about “spicy content” in particular, that allows users to feel so entitled to a premeditated fantasy; one that they came up with entirely in their own heads? For the bulk of these criticisms are not so much about the shoot’s technical aspects, but revolve largely around the “character” of Ari herself. Why isn’t she more confident, more elegant, more charismatic? As Hazel Hawke puts it in her After Dark review, “[I expected more] from an influencer who begins all her videos with, ‘So I’m a bop, I’m a mattress actress.’”

In response to this backlash, Ari has released a video defending herself:

God forbid a girl is nervous and awkward, making a movie like an hour after meeting someone. I honestly think that’s just my personality. Like obviously, on social media I can record things over and over again until it looks good. But in person, that’s just me. I saw a lot of comments saying my acting was bad. But I wasn’t acting; that’s just me.

It’s such that Ari finds herself at the center of an unwinnable paradox. On one hand, she’s adored for the persona she’s crafted online, as being authentic, vulnerable, and funny. Her fanbase consistently lauds her kindness, wit, and sense of humor, with many stating that they only subscribed to her OnlyFans after coming to love her non-sexual content.

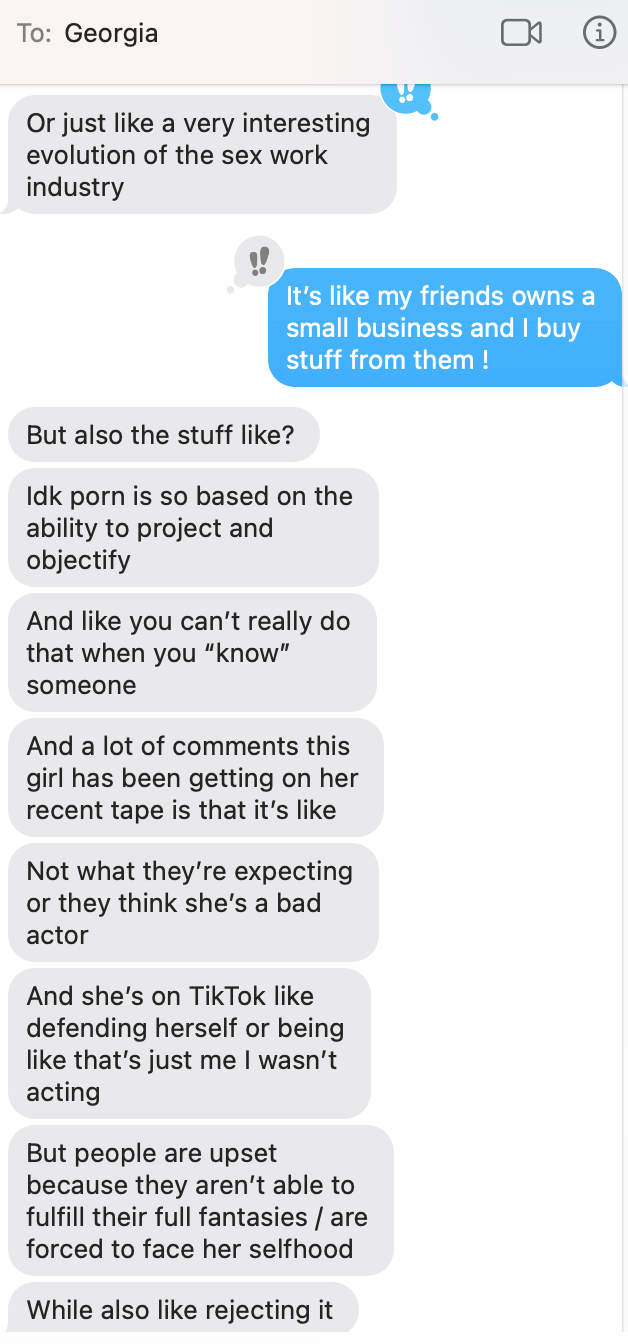

But when she’s “being herself” in an adult film, those very same fans feel betrayed. They loved Ari for being real. Until Ari was actually real.

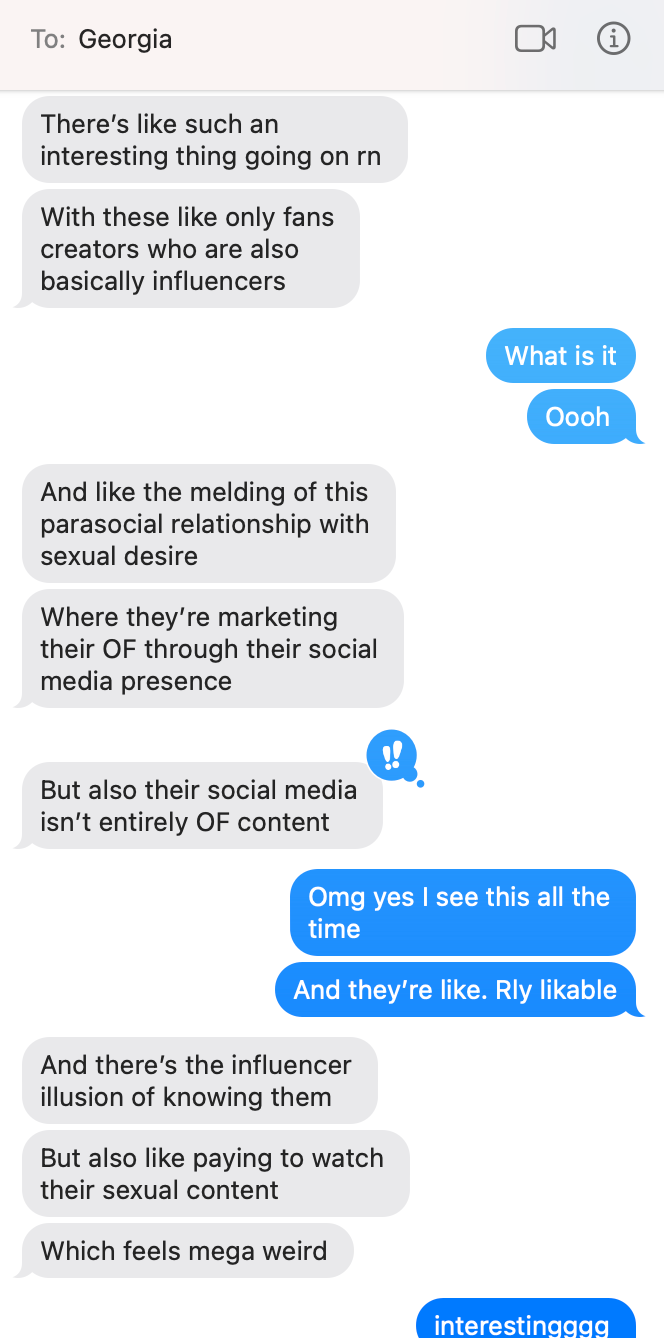

Thus is the trap of modern day porn production. With the advent of social media, and the guise of closeness it offers, it’s no longer enough to just be sexy. One also has to create and sustain a sphere of parasocial relationships; maintaining enough of a persona, both within and outside of sex work, that their audience can consistently project a set of fantasized ideals. In one video, Ari acknowledges that the product she profits from most is not just thirst traps or nudes, but her “personality”. In addition to being a sex object, bop, and mattress actress, she also has to be a #relatable friend, girlfriend, and crush.

And, as demonstrated by the backlash to her video, it’s not always easy to be both a sex object and human being at once.

Yes, her fans seem to say, be a full, complex, multifaceted human being – but not like that. Be sultrier. Be wittier. Don’t “yap too much” while giving head. (Indeed, this latter line is a frequent complaint on her last video).2 When her fans demand to see “the real Ari,” what they really want is for Ari to become, to fully embody, the alter-ego they’ve built up in their minds.

So what gives? Is it possible to ever package and sell intimacy without objectifying, commodifying, and ergo dehumanizing one’s full personhood and self? (Spoiler alert: I think the answer is YES).3

For context, there’s nothing new about exchanging intimacy for goods or services, either within or outside a capitalist economy. Nor is it unique to sex work.

Indeed, it’s so commonplace that feminist sociologists have, for decades, dubbed and studied a wide array of occupations as “intimate labor.”

This is widely defined as work that involves the management of interpersonal relationships, so that they “are – or give the impression of being – physically and/or emotionally close…private, caring or loving.”4 According to Viviana Zelizer, it usually entails some “knowledge and attention that are not widely available to third parties,” such as the sharing of secrets, confessions, or bodily privacy.5 This includes sex work, yes, but also nannying, nursing, masseusing, and therapizing. The list goes on.6

I name this only to say that there’s nothing inherently wrong about purchasing or bartering for intimacy. In fact, in a world that runs on the provision of intimate labor, it would be far worse to not compensate intimate laborers for their work. (As we do with, say, unpaid housewives). Especially when most people in the caretaking industry happen to be Black, brown, queer, and/or femmes.7

Where it becomes problematic (even dangerous) is when consumers forget that intimacy, paid for or not, does not equate servitude; that it requires give and take on both ends. Part of what makes human intimacy so uniquely precious is that it involves, at bare minimum, one other agent whose thoughts, desires, and needs are not the same as yours.

Outside the virtual sphere, for instance, clients are widely expected to respect the boundaries set forth by sex workers and escorts. If the needs don’t align, then you might cease being a client, sure. But it doesn’t give you license to berate, ridicule, and publicly mock someone for falling short of your fantasies, or to demand they push past their discomfort to meet your every need. (Doing otherwise puts you squarely in the realm of assholes, pricks, and, worst of all, sexual assaulters).

In other forms of intimate labor, moreover, such as elder care, therapy, and nursing, it’s integral to the job that laborers occasionally push back on their clients’ beliefs. Intimacy is not so much subjugation as it is ongoing trust and negotiation.

Regardless of whether it’s compensated, commodified, or freely given, all intimate relationships, by their very nature, involve some level of friction and imperfection. That’s just part of being human. Friends fight. Partners get heated with each other. Sometimes, sex workers feel awkward. That doesn’t make the intimacy any less authentic. If anything, it makes it all the more real.

As Ezra Klein puts it in his critique of online relations:

I think the friction of relationships between human beings is really important. As a person, it’s good for me that my wife does not adapt herself into whatever I want her to say. It is part of being a healthy human being that other people exist with friction to you.

So what is it about the online, parasocial relationship that leads people to expect frictionless wish-fulfillment?

In part, it stems from the way that virtual platforms have marketed themselves as a friction-free environment. If you don’t like something, you swipe it away. Each influencer, model, and actor is an expandable member of a constantly rotating cast. As soon as they fail to amuse, they’re gone! Online consumers are thus positioned as all-powerful arbitrators of value, whose sexual, intellectual, and emotional needs are met at little-to-no investment from themselves.

As a result, our tolerance for friction, and subsequent capacity for intimacy, is deeply diminished. The Ari x Girthmasterr controversy is only one example of how online spaces have warped our understanding of personhood, closeness, and care. Clients (i.e. consumers, users, or parasocial friends) feel entitled not just to a sex video, which Ari certainly delivered, but to the very person that is Ari Kytsya. Not only do they want access to her life, inner world, and vulnerability, but they want to grasp and mold that inner world toward their own tastes.

Brought to its logical and frightening conclusion, the video’s emerging notoriety has led to an influx of male stalkers showing up at Ari’s home. As “fan” entitlement is both enabled and encouraged through waves of online backlash – in which a shocking number of influencers have normalized leaking, pirating, or otherwise stealing Ari’s content – the social contract around intimate labor seems to be eroding.

The implications of this aren’t bad just for content creators, but for the consumers themselves, who seem increasingly ill-equipped for real, mutually intimate relations. For proof of this trend’s growing resonance, one has to look no further than Netflix’s latest hit series, Adolescence, which dramatized these dynamics to wide acclaim.

The show depicts how a young, lonely boy finds comfort through Instagram, porn, and online models, all of which condition him to feel increasingly entitled to and in-control of the women around him. It does a beautiful job of delving into the internet addict’s psych; demonstrating how online interactions have warped his worldview, obliterated his tolerance for friction, and thus strained his ability to develop genuine connections.

Both Adolescence and the Girthmasterr controversy are microcosms of a larger pattern that’s only going to get worse. The problem is not so much that intimacy itself is being marketed, sold, and consumed – indeed, intimacy and sex are, and have always been, invaluable forms of labor, for which workers ought to be compensated – but that social media has framed it as a one-way transaction, in which the consumer possesses exclusive control.

Notably, these problems only stand to be further exacerbated by a growing trend of what Connie Collins dubs “AI’s chokehold on intimacy.” As AI chatbots become increasingly trusted to fulfill consumers’ emotional needs – providing all of the dopamine reward with none of the emotional risk – intimacy risks being less and less about a collaborative interplay of differing desires, and more like one partner molding their very being into the shape of another’s fantasy. (For a visceral look at these dystopian, AI-generated dynamics, I strongly recommend Sam Kriss’ short story about “your beautiful submissive girlfriend”).

Given the landscape we find ourselves in, what are consumers, content creators, and intimate laborers meant to do? How can we develop alternative, healthier ways of relating to one another, in spite of all the ways social media has invaded our lives and shaped our most intimate dynamics?

Unlike thinkers like Jonathan Haidt, who’s often regarded as the key theorist in this area, I do not think the answer lies in banning social media. I’m all too aware of the relief that internet relations can offer queer, BIPOC, and disabled people with limited access to in-person communities.

I also don’t want to bash parasocial relationships wholesale. As someone who sleeps better when listening to her favorite podcast, I understand the genuine need that parasocial relations can fill, and that it’s possible to do so without compromising real-life relations. There’s nothing inherently harmful about OnlyFans, TikTok, or Instagram, so long as consumers have a baseline understanding of what relationships and personhood entail.

I do, however, believe that at the same time we make these virtual leaps forward, we must also put more resources toward creating opportunities for emotional development through in-person relationships. I’m obviously not the first person to call for third spaces, accessible community organizations, etc. etc. etc. Rather, I want to highlight how their absence has created the conditions for social media’s disproportionate influence on lonely users. Neither children nor adults should be receiving their primary emotional development from social media algorithms, in which their desires are the only thing that matters.

Anyways. If you’re still here, thanks for hearing me out, either in spite of or because you dis/agree with me. Feel that friction? It’s hot.

And as always, the golden rule of virtual intimacy is to support and compensate your content creators – so consider hitting the like and subscribe below <3

Many thanks to Georgia Chan for looping me into this TikTok drama and for providing the core analysis of this essay. See screenshots (below) for credit where credit is due xx

RT: for me, it was refreshing to see that even a drop-dead gorgeous mattress actress gets a little nervous during sexy time.

Notably, this problem is not unique to woman or femme sex workers. I could write a whole nother essay about how the fetishization of gay male porn stars is deeply tied to their content creator personas. Nor is it exclusively a problem perpetuated solely by men. Many of the critics in Ari’s comments happen to be women. In the words of one redditor: “As a chick who doesn't watch much porn and is genuinely just a fan of Ari... wtf was that?!?!”

Just in case it has to be said, this substack is unabashedly pro-sex worker!

Nicole Constable, “The Commodification of Intimacy: Marriage, Sex, and Reproductive Labor,” Annual Review of Anthropology 38, no. 1 (October 1, 2009): 49–69

Viviana A. Zelizer, The Purchase of Intimacy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

I hold that it’s impossible to create any firm definition that encompasses all of sex work, and which couldn’t also be applicable to other forms of intimate labor. Eroticism, physical touch, even biological reproduction is involved in a wide range of work that isn’t sex work. And with the definitions being so murky, how tf are you gonna demonize one subset of labor without inadvertently villainizing the rest?

Eileen Boris and Rhacel Salazar Parreñas, “Introduction,” introduction, in Intimate Labors Cultures, Technologies, and the Politics of Care (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010), 1–12.

As a former sex worker this is the paradox that plagues the industry— clients fall in love with the persona and the default premise of the work: you’re desirable because, regardless of boundaries etc, you present as a person with little to no needs. When that concept is confronted by glimpses of reality, the fault is with the provider for not upholding the fantasy. Just as in this case— it doesn’t appear anyone is chiding girthmaster for not doing a better job making Ari comfortable. She makes or breaks the fantasy without fully knowing the fantasy that fans have concocted.

This was an enjoyable read ! I just wanted to “provide friction” and disagree with the below statement.

“There’s nothing inherently harmful about OnlyFans, TikTok, or Instagram, so long as consumers have a baseline understanding of what relationships and personhood entail.”

These platforms are designed with the intrinsic feature of distorting relationships and personhood. They’re designed to be addictive, time consuming, and void filling.

On these apps, the person isn’t “real”. They are essentially a commodity providing a service, usually some false sense of connection, that people are willing to pay for.

Humans weren’t designed to process other human beings through a 2D screen in the same way they do in person.

This is why our behavior online (how we talk, present, and act) is drastically different from our behavior in person.

Don’t take this as me completely justifying the abuse that these women receive.

I’m just saying it’s unrealistic to partake in the exploitation of the human psyche and not expect the negative aspects of that exploitation to come along with it.

This is coming from someone who is building an online platform and understands what would come with it.